“The comfort zone is narrowing purely mathematically”

Since the end of February 2022, the Russian economy — partly forcedly — has embarked on the path of deep and irreversible transformations, which the Central Bank subsequently aptly defined as “structural transformation». This difficult and contradictory process continues today, on the threshold of 2024. Its final result is absolutely not obvious, but some intermediate results can already be summed up. We discussed the situation with Oleg Buklemishev, director of the Center for Economic Policy Research, Faculty of Economics, Moscow State University.

— The main success is, undoubtedly, maintaining the rate of economic growth in the positive zone (at the end of the third quarter, the increase in the Russian Federation’s GDP was, according to Rosstat, 5.5%. — “MK”). This means that growth is possible even in such conditions — not just difficult, but extreme. This is an important signal addressed both within the country and abroad. Well, the main minus is closely related to the plus. Behind all the quantitative achievements reflected in statistics lie very complex qualitative processes of structural adjustment, which in the future may negatively affect the development of the economy. The seemingly positive outcome was bought at a high price. The future is exchanged for the present at a greatly reduced rate.

— Undoubtedly, due to its market nature. We are accustomed to explaining economic success by energy resources, but in this case there is no need to talk about this: the volumes of raw materials exports and corresponding revenues to the budget are much weaker than last year’s figures, although overall they are not bad. Everyone saw that the economy is capable of responding to challenges, that its adaptation potential is quite high and that enterprises and businesses worked quite effectively in new conditions.

— Complex issue. Sanctions can be assigned a variety of tasks, and this, by the way, is described in detail in numerous theoretical works. No one expects an immediate effect from them, that the country that was subjected to them will immediately begin to behave differently. It would be naive to expect this. The main short-term goal of the West's sanctions policy towards Russia is to demonstrate its attitude to what is happening, and the long-term goal is to undermine the financial basis for conducting military action. Question: How will sanctions affect long time horizons? And here my expectations are not so optimistic: sanctions trigger a number of processes that are bound to work sooner or later.

— Only partly. Indeed, consumer demand plays a significant role in the unfolding economic growth. Since the Western manufacturer has left, there is no adequate replacement (in terms of price and quality), and parallel imports are expensive; in some cases, imported goods are replaced by Russian ones. Niches have become free in the market and are being filled with domestic developments, sometimes quite successfully. For example, among the sectors that are doing well today and are an example of successful market import substitution, I would include the production of furniture and food. What Polina Kryuchkova did not say (by the way, in a sense, my colleague is a graduate and then a teacher at the Faculty of Economics of Moscow State University) is the role of government demand. If we look at the structure of those industries that have flourished over the past year and a half, we will see quite a lot of its elements there. These are “metal products”, that is, mainly ammunition, the production of weapons, equipment, electronics and optics. The budget impulse, which affected these sectors and pulled the corresponding technological chains with it, is no less important in this case than consumer demand.

— The labor resource factor is the main limiter in today's conditions. Not only are demographic trends generally not the most favorable. Some of the workers were mobilized, some joined the army under contract, and in addition, there was a migration outflow: hundreds of thousands of our citizens left the country. In turn, due to the weakening of the ruble, difficulties began to arise with the influx of labor migrants. Those always have a choice — to go to Russia or somewhere else. And if they don’t like the exchange rate, they won’t go. No one is interested in earning money in rubles in order to receive “kopecks” in the currency that they can bring home. All these circumstances lead to a labor shortage and the impossibility of extensive economic development — simply by increasing or at least maintaining the number of workers. As a result, many sectors, including industry and the service sector, have undergone some personnel shortages. Here, by the way, there are also positive aspects: firstly, as a result of competition for workers, wages are rising frontally, which supports consumption, and secondly, there is a chance to update production, automate, digitalize, and increase capital investments aimed at replacing labor .

— Well, people didn’t switch to this mode yesterday. Having become accustomed to a certain level of consumption and lifestyle, many of those whose real incomes have declined (and the peak of real incomes in Russia was observed ten years ago, in 2013) are now trying to maintain them in dramatically changed circumstances. The population owes banks over 30 trillion rubles, but it is difficult to understand how much of this amount of debt is due to this kind of behavior. As for preferential mortgages, this is a special topic. The problem here is rather not so much the insensitivity of mortgage programs with a reduced burden of interest payments to the key rate of the Central Bank and the inflating demand for apartments, but rather a certain point of social injustice. In fact, only families belonging to the middle class can take advantage of the benefits (the poor still cannot afford a mortgage, and the rich do not need it). But meeting the housing needs of this category of the population is paid for by all taxpayers, which seems to me categorically wrong, when people below a certain level of wealth cannot take out a mortgage in principle. Moreover, when the share of the down payment will soon be increased. There is nothing good in the fact that today apartments are often purchased not for living, but for investment purposes.

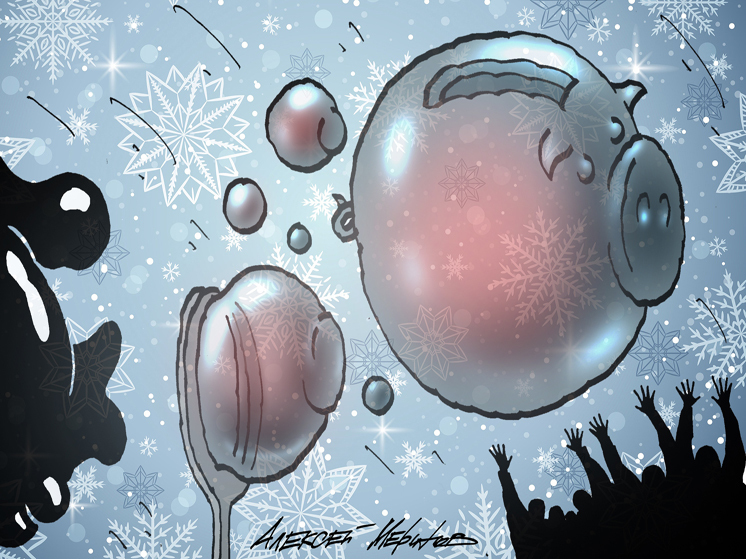

The usable area of the average apartment sold is decreasing from year to year, and the market is collapsing more and more qualitatively. Accordingly, the contradiction between the real incomes of families and their capabilities to improve their living conditions is intensifying. This long-term social problem is fraught with very unpleasant macroeconomic consequences. If a significant part of the population does not receive income sufficient to take out a mortgage (primarily market, not preferential), then who will the construction complex work for? When apartments in new buildings are bought not by potential residents, but by investors (for further resale), a bubble is inflated in the market, which at some point may burst. This is what the Central Bank, which clearly knows more than you and I, probably fears.

— In general, everything is logical. For a long time, our largest trade and investment partner was the European Union, now this place is occupied by the PRC. It is a growing power that has reached at least second place in the world in terms of GDP and has achieved significant economic success. The nuance is that many of our economic (and not only) processes become concentratedly dependent on one partner. Look at the foreign exchange reserves of the Central Bank — they are all entirely in yuan, there are no other foreign currencies there. The point here is not that China is somehow bad, we just need to diversify and have some kind of insurance in case the economic risks associated with such concentration materialize. China's 40-year period of extensive growth of 7% or more appears to be coming to an end. Our neighbor's economy is slowing down and may well present unpleasant surprises to those who are so dependent on it.

— Good question, but I don’t have an answer. Civilian sectors are used to taking care of themselves, which is what they are now trying to do. Much of the success in the economy was achieved precisely thanks to their market steps taken under severe restrictions. Companies and enterprises looked around and unexpectedly found out that sometimes they have someone to replace their previous foreign suppliers, and that new potential partners are in some cases no worse, at least in terms of price attractiveness. There are many examples of this kind of structural transformation, the transition of the economy to a different state. For some it is easier, for others it is more difficult (for example, for the auto industry), everyone is in a different situation: some depend more on imports, some on blocked exports, and others on government demand. Another thing is that in the economy and society there are areas of primary responsibility of the state. This is, for example, the development of human capital, where it is imperative to increase investments in order to look forward with confidence. However, today we are seeing rather the opposite processes. Medicine, education, science — all these areas should be rapidly supported by the state, but in reality they are in a frankly disadvantaged position due to the low priority of budget allocations. And in this, in my opinion, there is hidden a mine of enormous destructive power under the future of Russia.

— There are enough worries. For example, we see how the West has literally begun a hunt for the tanker “shadow” fleet, that the United States is planning to “kill” the Russian Arctic LNG-2 project, that there is a growing shortage of equipment for the oil refining industry in the country, that imported aircraft engines are running out of resources, that electronics are increasingly failing in passenger cars imported through parallel imports. This is the news flow today. And the further we go, the more similar, purely physical restrictions there will be. We either cannot cope with them, or this requires the expenditure of a huge amount of resources and a fair amount of effort. Our country has not yet reached the high road in its economic development, as it continues to struggle with constantly tightening sanctions. Yes, we can say that they are ineffective, that the goals set by their authors have not been achieved. But Russia is still in the position of a beast being hunted down by a group of hunters. Moreover, they constantly change their tactics: okay, you didn’t fall into a trap here, but we’ll build a new one in another place, more cunning and sophisticated. This is an interactive process, it is a tunnel, at the end of which there is not light, but rather a dead end.

In general, don’t be mistaken: when a certain set of restrictions applies to you, you obviously don’t become better, more productive, or get closer to your optimum. We are talking about a purely mathematical narrowing of the comfort zone. So sanctions, by definition, cannot benefit the Russian economy: they “break it down” in every possible way, seriously hindering development.

—I won’t say that we are leaving or have already gone into the wilderness isolation. The contribution of foreign trade to Russian GDP is still very large. Our economy remains open, connected by a variety of (albeit more crooked) chains with the world market, in which we continue to be present. Russia still has a market currency. It is extremely difficult to cut yourself out of this global system. At the same time, we are clearly far from the optimal state. In a situation where the economy needs advanced technologies, modern equipment, and relevant competencies, our businesses have to deal with not the best models, with not the most developed and geographically close trading partners, who sometimes provide less choice and pay worse. We are forced to constantly reinvent the wheel where it has long been invented.