The creator of the modern tax system: what legacy did the famous politician and economist leave

Exactly 10 years have passed since the passing of Alexander Pochinok, one of the most prominent statesmen of the nineties and zeros. Alexander Petrovich burst into big politics on the wave of perestroika congresses of people's deputies, which the whole country watched on TV, and stayed in the corridors of power for a long quarter of a century. He managed to be a people's deputy, a member of the Federation Council, worked in the government, headed the tax service, and was the minister of social policy. And all this in the most difficult times for Russia of political change and economic reforms. His heart stopped beating on March 16, 2014. The repair was only 56 years old. On the eve of the mournful date, Alexander Petrovich’s wife Natalya Pochinok told MK what her husband was like and what mark he left on the history of modern Russia.

Alexander Pochinok at a press conference at MK.

Alexander Pochinok at a press conference at MK.

— It was the year 1990: there were public broadcasts of meetings of the Council of People's Deputies of the RSFSR. The whole country was glued to the TV and watched them for hours on end. “This Pochinok is at the microphone again, he doesn’t even go back to his place. He performs within the regulated 2-3 minutes and again gets in line to perform,” my mother exclaimed. “He’s so smart, he has something to say on any issue.” That's how I learned about its existence. He was then a little over thirty, I was fifteen.

We met in the fall of 1997 in his office on Neglinnaya Street. Plekhanov University attracted famous officials and politicians to teach students. And here we have such luck — there’s even a whole head of the State Tax Service. Me and another excellent graduate student were given to Professor Pochinok to help conduct seminar classes on the course. I remember he was sitting at his desk, covered with a pile of papers and a pile of books. We were directed to sit on side chairs. Pochinok had a neat haircut, a wide smile on his face, and kind eyes. It was a mutual spark at first sight. There were three people in the room, but he only had a dialogue with me. Instead of discussing seminar plans, it turned out to be a thorough lecture, rich in real-life examples, on the history of the creation and development of the tax system of modern Russia. But then I couldn’t even think about anything other than work. I was 21 at the time, he was 39; He didn’t have a wedding ring on his finger, and I asked a colleague if he was married. They started dating only a year and a half later, when it became completely clear that this was not a hobby, but a real feeling. We got married in March 2000.

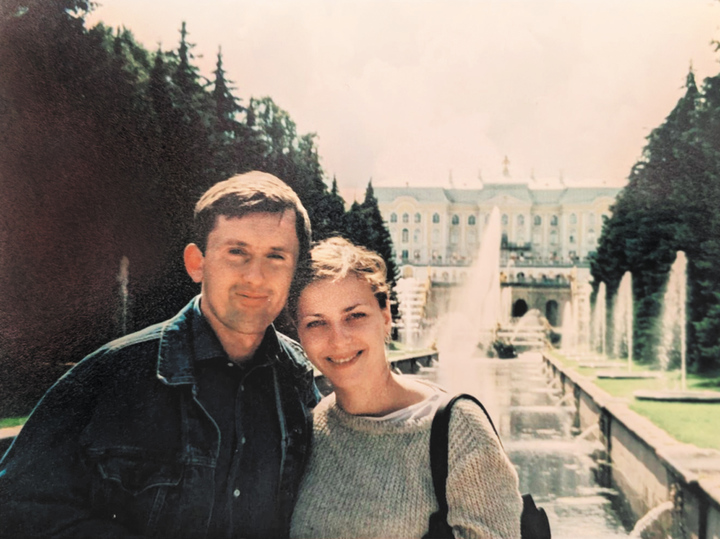

Spouses on vacation in Peterhof. 2002 < /span>

Spouses on vacation in Peterhof. 2002 < /span>

< p>

— It’s no secret that the modern tax system, adopted by Russian laws in the early 90s, is a model system of European countries. But it was impossible to simply copy everything, Russia is a federal state with three levels of government: federal, regional and local. And all levels had to cut either individual taxes or shares of tax deductions. This work was headed by Pochinok. When the time came to make personnel changes in the State Tax Service (then the Federal Tax Service was called), he became the main candidate for the position of its head. Like, he wrote the laws himself, collect taxes for the budget himself, organize so that the tax system works in the country. By the way, a flat personal income tax rate of 13% was his idea. “The rich don’t pay anyway, but everyone will pay,” he defended this concept.

—Once, I remember, he brought home a poster with the inscription “Pay taxes and live” with an image of Freddy Krueger from a popular Hollywood horror film at that time and grinningly said: “Look, what the devils came up with, they are not shy, they demonize. Recently in Voronezh they burned an effigy with my face on it! They don’t want to pay taxes and they are inciting ordinary people.”

In fact, at that time small businesses were in the shadows, and the main taxes were paid by large businesses, mainly those who extracted and sold natural resources for export. And these are companies that knew everything; they could be counted on one hand. It was necessary to negotiate with them, and it was the minister with the business owners, in order to get the necessary amount into the budget. At that time, there were no electronic declarations yet, tax records were kept on paper, and so craftsmen appeared who allegedly exported goods abroad in order to avoid paying VAT and also receive a refund from the budget of a large part of it. But the goods did not go anywhere, documents, contracts, even stamps about crossing the customs border were simply falsified. They tried to steal colossal sums from the budget. I had to “tighten the screws” and look at every export operation where a VAT refund was claimed under a magnifying glass, and fight for the country’s tax revenues in the courts.

Even at that time, vodka makers were playing pranks. They printed fake excise stamps — you couldn’t tell them apart from the real ones. And the then-famous alcohol magnate Bryntsalov ordered millions of excise stamps from the state for checks, and glued them onto standard-sized bottles: they looked the same, the only difference was in the barcode numbers. Pochinok later recalled that story with a laugh, although it gives an idea of what issues had to be resolved then.

— In 1999, as part of the modernization and digitalization of tax accounting and social contributions of citizens, it was decided to introduce an individual taxpayer number (TIN). Now this seems like an obvious solution, but at that moment it resulted in a real confrontation and there were popular unrest. Even the highest ranks of the Patriarchate joined the fight against the INN; they publicly called the identification numbers a devil’s mark. Passions became so heated that the minister had to bring this issue to special hearings at the Trinity-Sergius Lavra within the walls of the Moscow Theological Academy with the participation of His Holiness the Patriarch. There an official decision was made that there was no diabolism in the INN.

— Yes, it turned out to be a great PR move. Everyone still remembered for a long time how Pochinok, in the ceremonial general uniform of a tax chief, took on the full color of our stage. And this color, led by Alla Borisovna, promised in front of a television camera that it would pay taxes on its fees. And, by the way, they started paying. Pochinok regularly checked the statements. The artists respected him.

— Yes. Soon after President Yeltsin resigned, Pochinok was unexpectedly appointed Minister of Labor and Social Development. I remember being indignant: “Give up! You are a specialist in economics, budgets and taxes. You’re not a woman, after all, to deal with social issues.” But I was completely wrong. After all, what he managed to do during his four years as minister became the foundation of the modern social protection system. Judge for yourself: in 2000, the law on the minimum wage (minimum wage) and laws on labor guarantees and social protection were adopted. At the end of 2001, the Labor Code was adopted, in 2002 — pension reform and the emergence of insurance and funded pensions, and in 2004 — a complex law on the monetization of social benefits. Now, after 20 years, all this is perceived as the foundation of the modern social system of the state, but then it was risky steps into an unknown future. It’s impossible to count how many “Pochinok effigies” were burned by opponents of transparent individual measures to support the population. By the way, it was under him that Social Worker Day was established, which has been celebrated in Russia for more than 20 years.

Monument at Novodevichy Cemetery.

Monument at Novodevichy Cemetery.

—This is true. Pochinok was not part of this or that clan, as they say now. That’s why I worked with different leaders in different governments and legislative bodies. Some of the leaders relied on him and trusted him; someone was jealous of his intellectual abilities, efficiency, strong, loving family.

Pochinok was a difficult official. He has been through the millstones of real election campaigns more than once. In that era, there was still no Internet and electronic voting; it was necessary to communicate a lot with people, prepare real action programs, and, if elected, prove one’s worth through deeds and keep the word given to voters. He said that during the election campaign for the Supreme Council and the Duma, he campaigned on city buses and trams, walked along the streets and courtyards, met people and always greeted them with a handshake. He was a famous person in the Chelyabinsk region, many recognized him and wanted to talk to him. He was never a “pompous turkey” from power, he loved people, knew their needs and concerns.

Many years later, being a big boss in Moscow, he calmly rode the metro — he said that it was faster. Although at that time he already had a car with a flashing light. I think it was a good habit to stay close to people and not grow a halo over your head.

— To be honest, he was very sad that he was not invited to the government, despite the fact that he was in the prime of his life, with vast experience and many ideas needed for the country.

At the same time, he dreamed of returning to his native Chelyabinsk as governor and making a leading region. No doubt he would have succeeded. And they were waiting for him there too. In 2012, oligarch Mikhail Prokhorov decided to play politics and created his own party, the Civic Platform. Pochinok became part of the 11-member Federal Political Committee with responsibility for the social block. «Why do you need that? — I asked one day. “You’re the only one there who has professional experience both in politics and in matters of public administration.” He replied: “Because this is a direct channel to convey to the very top what and how needs to be changed in the country.” He hoped that this would bring him a place either in the State Duma or as governor in Chelyabinsk. But this was not destined to come true…

And a year before his tragic death, the rector of Plekhanov University invited him to head the department of taxes. “Go to the department too, help,” Pochinok told me. It was nostalgia for the years of almost fifteen years ago, however, it was no longer a professor-graduate student, but a department head-professor. We called each other by our first and patronymic names in public, wrote scientific articles and study plans. The academic council of the university was scheduled for Monday, March 18, where Alexander was supposed to be elected head of the department for a new term, but on Saturday night he passed away. I replaced him in this post.

“He had the nickname “a walking encyclopedia”; he had an answer to any question. He read a lot, especially loved books about military history. He collected old books. There was an excellent guide and storyteller. We never even took guides on our trips, because Pochinok was still better both in terms of the volume of information and the format of an interesting presentation. He was an expert in many matters: books, winemaking, travel, ships (he knew their structure and modifications).

But he didn’t drive a car. He was never able to learn, despite my numerous attempts to teach him. I was the driver, and he was an excellent navigator.

He loved to communicate with journalists, and they loved him too. It is no coincidence that he was a regular on the main political and economic talk shows on television. He always spoke clearly, to the point, without empty chatter.

I didn’t like to play sports, except chess. I played with pleasure online, by the way, under my account. He often won and then joked: “Look, I earned you such a high rating!” And the most complex sudokus clicked like nuts.

I loved home cooking: borscht, cheesecakes, steak. If we went to a restaurant, I preferred sushi with beer.

He believed in God and always wore the cross with which he was baptized as a child. Therefore, a few months after the civil wedding, we got married in Raifa.

— Now the eldest, Peter (we named him after his grandfather, and he is a copy of his father in appearance and manners), is 23, and the youngest, Alexander, is 21, he probably looks more like me. They were 13 and 11 years old respectively when their father died, they remember him well. He spent almost all weekends with the children, told them many instructive stories, educated them, never raised his voice to them, and if they didn’t listen, he tried to explain to them how to do the right thing. He also spent a lot of time talking with his daughter from his first marriage, Olya; she also looks exactly like her father. The relationship between all the children is very friendly, the boys love their older sister very much.

Both sons served in the army. Senior in the honor guard company of the Preobrazhensky Regiment, took part in the anniversary parade on Red Square in 2020; and the youngest is in the Airborne Forces. Now they are students. The eldest is graduating from the Russian University of Transport with a master's degree in big data, and the youngest is graduating from the IT faculty of Baumanka. They grew up well, unspoiled guys, their father would be proud of them!

— He has not been with us for 10 years. Pochinok is buried at the Novodevichy cemetery. The tax minister's bronzed jacket is carelessly thrown over the parapet, and his cap is also there. The open unfinished book on taxes “Fiscal” and his words, spoken shortly before his death at an open lecture at the university, are engraved in stone: “Our country has a bright future. Russia has the main wealth. She has a bright and talented younger generation. I believe in it». And I believe in this and really want him to be remembered as a Russian economist, the creator of the modern tax system.