The discovery may change views on the diet of ancient people

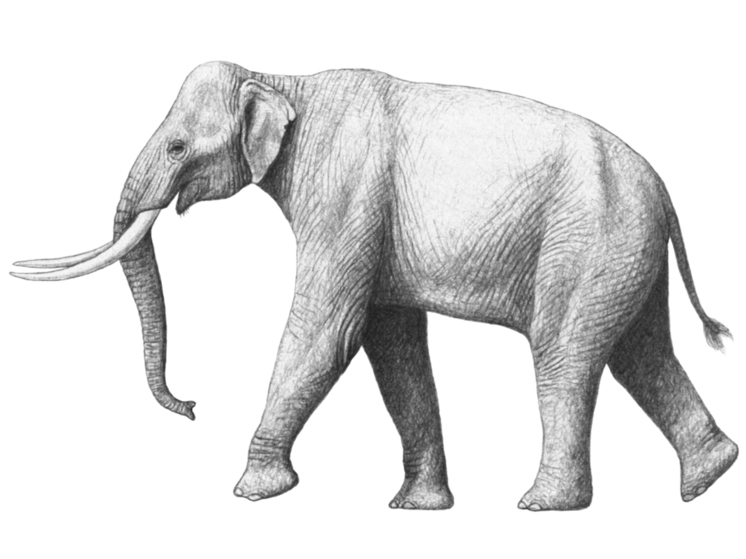

Despite its name, the mammoth was not the largest land animal of the Pleistocene. This status belongs to its relative, the straight-tusked elephant Palaeoloxodon, which, weighing up to 13 tons, was twice the size of the modern African elephant and lived in Asia and Europe about 100 thousand years ago. Anthropologists have been looking for evidence that Neanderthals hunted prehistoric giants even before extinction, but the evidence was mixed until a recent discovery that could change our understanding of the social structures of our closest extinct relatives.

Palaeoloxodon is believed to have survived ice ages in southern Europe and the Middle East for approximately 700,000 years, expanding its range into central Europe during interglacial periods. Their enormous size means that at least the adults were probably more threatened by food shortages than by predators until they stumbled across one who knew how to wield weapons and work as a team.

Although Neanderthal skills in the manufacture of tools allowed them to cope with paleoloxodon, this in itself does not prove that they hunted it.

“Fighting an enraged beast of that size would be a terrifying ordeal, even with spears, and might not be worth it if most of the meat had to be left behind,” — scientists think. However, in a recent study by Sabine Gaudzinski-Windhäuser from the archaeological research center MONREPO, a team pointed to numerous cut marks on the bones as evidence that elephant was part of the diet of Neanderthals.

Evidence of this comes from the Neumark Nord 1 site near Halle, Germany, where 3,122 bones, tusks and teeth believed to belong to more than 70 straight-tusked elephants, some 125,000 years old, were found. Gaudzinski-Windhäuser found cut marks on many of the bones that could only have come from stone tools used to cut away meat.

Although eating elephants killed by other means may leave the same marks as butchering those that were hunted, the concentration of so many bones in one place makes this unlikely. Moreover, the bones overwhelmingly belonged to adults that would have been unlikely to have been targeted by even the bravest saber-toothed felines of the time, and this could not have arisen by chance. It appears that these Neanderthals preferred to hunt bulls, which weighed twice as much as the largest African elephants but were probably solitary, rather than hunt herds of females and calves.

The authors estimate that it would have taken a team of Neanderthals working together several days to butcher such a beast, let alone process it all. Since neither humans nor our mushroom-loving relatives can live on meat alone, it would take a large family of 25 people three months to eat it all.

Experts believe that if hunters didn't go to all these lengths only to waste most of the food, it indicates that at least some Neanderthals lived in larger groups than previously thought. The article suggests that they either stayed in one place for a long time, acquiring the skills of drying or freezing meat, or that several tribes came together to dig traps and feast on the spoils for weeks. Such activities would greatly facilitate cultural exchange.

People living in one place and collecting vegetables to serve with an elephant roast may have changed the local environment more than previously thought. This does not mean that elephant hunting was widespread among Neanderthals.

«It is becoming increasingly clear that Neanderthals were not a monolith and, unsurprisingly, possessed a full arsenal of adaptive behaviors that allowed them to excel in a variety of ecosystems of Eurasia for more than 200 thousand years,” — explains archaeologist Britt Starkovich.

The find also changes views on numerous other sites where bones of mammoths (half the size of Palaeoloxodon) and even smaller rhinoceroses have been found mixed with Neanderthal tools. The idea that Neanderthals simply killed off these large animals seems less likely in light of this discovery.