An alternative history of the end of the first Cold War and a forecast for the course of the second

Sometimes the policy statements of world leaders aimed at their own and others are presented in elegant, almost poetic language. 1961, inaugural speech of the new US President John F. Kennedy: “Let every state, whether it wishes us good or evil, know that we will pay any price, endure all difficulties, overcome any trial, support our friends and stop our enemies for the sake of salvation and strengthening freedom.» And sometimes such statements use emphatically business-like, even down-to-earth language. But this does not reduce, but even further enhances the volume and persuasiveness of the political signal conveyed in this way. 2024, Vladimir Putin explains the reasons for the change of shifts in the Russian Ministry of Defense: “In the Soviet Union in 1985-1986, defense spending amounted to 13%. For us today, taking into account the state of the economy, macroeconomic indicators, and budget revenue forecasts, spending on defense and security together at just over eight percent is uncritical, absolutely normal. Moreover, experts believe that even more could be added there. Budget possibilities, according to these experts, allow. But they are what they are.”

Vladimir Putin knows how to create a deeply layered defense system and calculate his actions several moves ahead.

Vladimir Putin knows how to create a deeply layered defense system and calculate his actions several moves ahead.

The appointment of Andrei Belousov as the new head of the Russian Defense Ministry was widely interpreted in Russia and abroad as an indication of Moscow's readiness to conduct the Cold War as long as necessary. The correct explanation is correct, but very incomplete. Vladimir Putin analyzed the reasons why the Soviet Union lost the first Cold War — or voluntarily and unilaterally disarmed itself in front of the enemy, which in its long-term consequences turned out to be equivalent to a crushing defeat. The result of this «work on mistakes» was a fundamentally new political philosophy, a strategy that will determine the entire course of Putin's presidential term that has just begun. Belousov's appointment is, first and foremost, the «thread» that, by unraveling it, we will be able to understand what exactly VVP has planned.

Each of us knows the chain of events that led to the violent conflict in Ukraine. The West’s sworn promise to Gorbachev to renounce NATO expansion to the east in exchange for Moscow’s consent to the unification of Germany and its inclusion in the North Atlantic Alliance — Mikhail Sergeevich’s naive willingness to believe in these assurances of his “partners in new thinking” — the West’s withdrawal into complete refusal in the style of “ you didn’t stand here and anyway, citizen, I don’t know you” — Moscow’s current efforts aimed at restoring the geopolitical balance in Europe.

1986, Mikhail Gorbachev's visit to the GDR. The Berlin Wall still stands, but “the clock is already ticking”: the West won the economic competition and this predetermined everything else. Photo: German Federal Archives

1986, Mikhail Gorbachev's visit to the GDR. The Berlin Wall still stands, but “the clock is already ticking”: the West won the economic competition and this predetermined everything else. Photo: German Federal Archives

But as is clear from Evgeny Primakov’s story to his friend and ally, the current president of the Institute of World Economy and International Relations, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences Alexander Dynkin, there was a very significant nuance in this story. At the time Gorbachev made the fatal decision, Yevgeny Maksimovich was already a member of the senior Soviet leadership. And this is what, as Alexander Dynkin told me, he tried to do: “Primakov knew the West very well, was not naive, and because of this was inclined to be distrustful of its promises. Therefore, he proposed leaving several Soviet military bases on German territory as a guarantee of the reliability of his partners’ words.” The further development of this story is partly easy to guess: Mikhail Sergeevich did not approve of the idea. But the Secretary General had a completely unexpected ally in this regard.

Alexander Dynkin: “The then Soviet military leadership also spoke out categorically against Primakov’s proposal. This position was motivated by the fact that Soviet troops should not be permanently stationed on the territory of a foreign state with a fundamentally higher standard of living than in the USSR. If this suddenly happens, then the moral decay of our troops will not take long to occur. Anything that can be stolen will be stolen quickly.” A fantastic story — and one that explains a lot: both in terms of understanding why the Soviet Union lost the first Cold War, and in terms of understanding what Russia must do in order not to lose in the second.

Evgeny Primakov called not to take the West’s word for it and to leave several Soviet military bases on the territory of Germany. Photo: Boris Prikhodko/RIA Novosti archive/wikimedia.org

Evgeny Primakov called not to take the West’s word for it and to leave several Soviet military bases on the territory of Germany. Photo: Boris Prikhodko/RIA Novosti archive/wikimedia.org

Well-known expert and dean of the Faculty of International Relations at MGIMO Andrei Sushentsov likes to use the term “strategic thinking vacation” to describe the behavior of the current European political elites. But when I asked Andrey about the origin of this term, he answered me: “I heard this metaphor in a conversation with a former British diplomat.” So, “strategic thinking vacation” is a Western term. And this has its own homespun truth. Another domestic expert, professor at the Faculty of World Politics at Moscow State University Alexey Fenenko, recently published an article “The Inertia of Pacifism,” which describes in detail how strategic thinking in our country increasingly “went on vacation” in the last decades of Soviet power.

Reading this article was painful for me almost on a physical level. Many of the “basic brain settings” of our political class, which Alexey Fenenko notes with ruthless precision, successfully survived the collapse of the USSR and migrated to our post-Soviet reality: “The thinking of the expert community in the USSR was oversaturated with moral and value categories: “progressive — reactionary”, “fair” “unfair”, “right is aggression” and so on.” But we didn't just think that way ourselves. At the same time, we did not yet understand that “domestic and Western experts have different views on the nature of international relations.” We transferred our “normative Soviet perception of the world onto the worldview” of Westerners, believing that they also looked at the world based on a similar coordinate system.

However, as Alexey Fenenko again notes with ruthless precision, in reality everything was completely different: “For the Anglo-Saxon elites, brought up in the categories of political realism, this Soviet moralizing was strange. What is justified is what benefits us, and what does not bring it should be eliminated or reprogrammed for our benefit. For them, liberal rhetoric was either a way to gain access to resources or a form of their own power.” The further, the more this fundamental difference in worldview undermined the USSR’s readiness and desire to wage the Cold War. Thus, we came to a situation where on the other side of the barricades they played in earnest, but on our side they played for fun. But such a statement gives rise to a new question: what exactly gave rise to such a difference in views on the world and how it actually works?

Alexey Fenenko believes that the whole point here is the “pernicious influence” of pacifism — or, as it was called in the Soviet era, the “struggle for peace”: “At the level of mass consciousness, the idea “if only there was no war” was introduced… However, little who thought that this phrase might have an unpleasant continuation: “If war is the worst thing, then to prevent it you can capitulate, especially if the capitulation is formalized in an honorable form.” From here gradually grew the idea of the need to “throw off” first regional conflicts, then the “Third World”, then the socialist camp.” I understand this logic, but I am ready to argue with it. In my opinion, we cannot reduce everything to ideology and forget about economics.

During my life, I have read a lot of memoirs of Soviet politicians, artists and other “lucky” people who had the opportunity to visit the West in the last decades of the USSR’s existence. And in each of these books, in different words, the same phenomenon was described — a terrible shock, a real revolution of consciousness, which inevitably occurred in the author at the moment of their first meeting with the Western world. Soviet citizens were brought up in the belief: our country is the best, the most advanced, the fairest, the most well-equipped. But all these ideas were broken into small fragments at the sight of shops filled with goods, elegant streets and well-equipped life.

“Public education plays a decisive role in war… When the Prussians beat the Austrians, it was a victory of the Prussian schoolteacher over the Austrian schoolteacher” — this is how in 1866 the famous German geographer Oskar Peschel explained the reasons why Berlin crushed Vienna during their war conflict. During the first Cold War, the architects of the Western economic model played the role of the “Prussian schoolteacher.” The shock described in the previous paragraph was a first-order phenomenon that began to gradually reprogram the brains of the Soviet elite. This is what I think the main stages of this reprogramming looked like. First, painful attempts to understand why it is so for them, but not so for us. Then a gradual coming to the conclusion that the West is a model to be followed: we must become the same as them! We must catch up with them!

And from this conclusion there is a direct road to another: we were told that the West is bad, that there is poverty, exploitation of man by man. But in fact, we see something opposite: in comparison with living conditions in the West, we have poverty and exploitation of man by man! And if so, then the West cannot be bad! The West is good! You have to put up with him at any cost, you have to be friends with him! This is how history sometimes has “black humor!” The ideology of Marxism-Leninism, which was dominant in the USSR at the official level, de facto acted at the final stage of the Cold War as a very effective and spectacular ally of the West — and, by the way, in more than one respect.

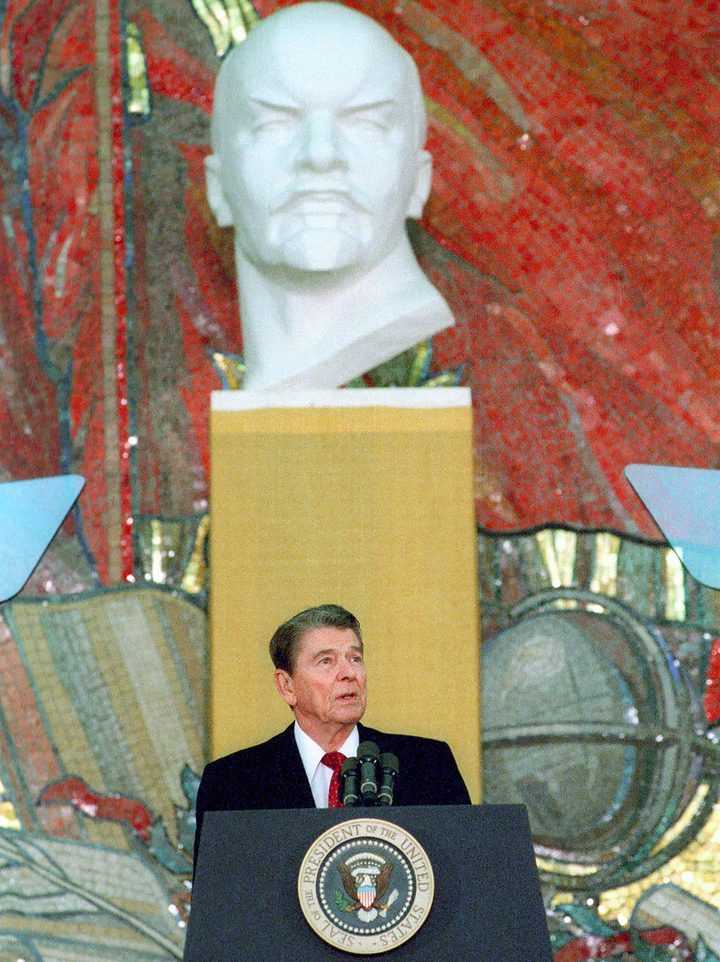

At the final stage of the First Cold War, the ideology of Marxism-Leninism de facto became an ally of the West. Photo: White House Photographic Collection

At the final stage of the First Cold War, the ideology of Marxism-Leninism de facto became an ally of the West. Photo: White House Photographic Collection

Seven decades of isolation of Soviet citizens from the theory and practice of market relations (okay, a little less — in the 1920s the USSR still had NEP) led to the fact that by the time the collapse of the Soviet Union even the most advanced residents of our country were “first-graders” ”, who did not even understand the basics of how the entire surrounding non-communist world works economically. Fragment from the book by Evgenia Pismennaya “By and large: essays on the history of the Central Bank of Russia”: “The Deputy Prime Minister for Economics in the first Yeltsin government was Gennady Filshin, who during the six months of his work became famous for promising two English citizens, Paul Pearson and Colin Gibbins, sell 140 billion rubles in cash. He said this: we need to withdraw money to Zurich, where there is the only cash market in Europe, and bring back 7.8 billion dollars. Matyukhin (Chairman of the Central Bank of Russia. -), having learned about such an initiative of the government, was simply dumbfounded: how can one seriously consider the proposal to export 140 billion rubles in cash when the turnover of the entire Soviet Union is 70 billion?

Now, in an era when the British The Economist criticizes Elvira Nabiullina for having too successfully (from a Western point of view, of course) mastered the rules and norms of a market economy, pushers of such ideas would not even be allowed into the entrance of the Ministry of Finance or the Central Bank. But in that naive era, Gennady Filshin’s idea was seriously considered at government meetings. In the end, through the efforts of more competent people — such as Georgy Matyukhin — the adventure was stopped. But the question is: how literate were these “more literate” people? It looks like not much. Another fragment from the book by Evgenia Pismennaya is about the meeting of the first head of the Central Bank of Russia with the long-time chairman of the Central Bank of France Jacques de Larosiere in 1991.

«Matyukhin spoke firmly and confidently. Everything seemed obvious to him. There is no other way: the republics must switch to their own currencies. It is so natural. Only separation from the USSR can give the opportunity to develop further. But Jacques de Larosière did not understand him. «No, no, you can't do that. It would be a huge mistake,» the French central banker gesticulated heatedly… «Don't be stupid!» the French head of the Central Bank did not calm down. «We in Europe have spent so much time developing a single currency and still have not created it, and you, having a single currency, want to destroy everything? I don't understand. It would be the greatest stupidity.»

Let us summarize the preliminary results. Our country lost the first Cold War thanks to economists — in the sense not of technical specialists, but of ideologists of economic policy. Russia will be able to avoid losing the second Cold War only by relying on the same (correction: not the same, by no means the same) economists. And one of the main roles among these economists should be played by the new Minister of Defense Andrei Belousov.

“Only now I took a little breath and looked around in the minister’s office. On the wall are portraits of V.I. Lenin and M.S. Gorbachev, at the entrance there are busts of Suvorov and Kutuzov. Big globe. A special table for working with maps. Bookcases with classic works and reference literature. Meeting table and work desk. Newspaper reading desk. Communication console… Everything is familiar, seen many times, and everything seems to be for the first time. This is where I should work. I never thought that I would occupy such a high and responsible position in the state,” this is how Yevgeny Shaposhnikov described in his memoirs his first feelings after his unexpected appointment to the post of Minister of Defense of the USSR in August 1991.

Andrei Belousov (pictured two days after his appointment) is helped to get up to speed as Minister of Defense by the works of his late father, the famous economist Rem Belousov. < /span>

Andrei Belousov (pictured two days after his appointment) is helped to get up to speed as Minister of Defense by the works of his late father, the famous economist Rem Belousov. < /span>

We do not yet know (and it is not a fact that we will know at all) what Andrei Belousov felt at the time of his appointment as head of the Russian defense department, when exactly he learned that such an appointment would happen, and whether he saw himself in this position before. But we know another absolutely amazing fact. The father of the current Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation, the famous Soviet and Russian economist Rem Belousov, died at the age of 82 back in 2008 — at a time when his son Andrei served as director of the department of economics and finance of the Russian Government and had just begun to gradually enter Vladimir Putin’s inner circle . But this did not stop Rem Aleksandrovich from leaving as a legacy to his son — and also to everyone else — a carefully crafted document, which, if read from the perspective of today, looks like detailed instructions: what the Russian Defense Minister should and should not do in order to provide the country with a result of the military conflict that is comfortable for her.

“Tell me who your teacher is, and I will tell you who you are” — in my opinion, this “corrected” form of the famous aphorism is no less accurate than its classic version: tell me who your friend is and I will tell you who You. When I asked knowledgeable people who should be considered Andrei Belousov’s teachers and mentors in the profession, they told me the same names. This list of teachers includes, for example, the late academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, long-term director of the Institute of National Economic Forecasting of the Academy of Sciences Yuri Yaremenko, academician of the USSR Academy of Sciences Alexander Anchishkin, who died very early, and USSR State Prize laureate Emil Ershov. But these are all second and third place holders. Andrei Belousov's main teacher, his, so to speak, spiritual and professional father was the direct parent of the current Minister of Defense — Doctor of Economic Sciences Rem Belousov.

Teachers and mentors of Andrei Belousov: academicians Yuri Yaremenko and Alexander Anchishkin.

Teachers and mentors of Andrei Belousov: academicians Yuri Yaremenko and Alexander Anchishkin.

Rem Beloussov lived a long and eventful life: he participated in the Great Patriotic War as an aircraft gunner, graduated from MGIMO, worked in the economic department of the USSR embassy in Berlin, participated in the development of economic reforms in the team of the Chairman of the Council of Ministers Alexei Kosygin, served as an economic adviser to the leaders of Vietnam and Laos. And after retirement, Rem Beloussov began writing the main book of his life — «Economic History of Russia in the Twentieth Century» in five volumes. Today, this five-volume work is a bibliographic rarity that cannot be bought for any money. And this is simply the greatest injustice. Rem Beloussov's book is not something «fundamentally abstruse». Rem Beloussov's book is written in a very clear, tasty, juicy and understandable language and is not so much an economic as a political and economic history of our country in the twentieth century.Rem Aleksandrovich shows the relationship between fateful political and management decisions and the reaction of the economy to these decisions, how this relationship either gives the country a powerful impetus for development or knocks it down. And here is a clear example for you. The names of the chapters and chapters of that part of the book by Belousov Sr., in which he writes about the First World War. “Chapter five. The war deforms and destroys the economy: the Russian economy cannot withstand overloads — Protracted mobilization of industry — The beginning of the food crisis: a gap in the weak link — The monetary system and the budget turned out to be more durable. Chapter six. The aggravation of economic contradictions leads to a social explosion: belated restructuring of economic management — Political parties enter into a struggle for power — Catastrophe.»

Reading not the table of contents, but the book itself by Rem Belousov makes an even stronger impression. Here are a couple of quotes I chose almost at random. Belousov Sr. on the problems of military production: “The main obstacle to the expansion of military production was the shortage of raw materials and fuel. This global disproportion increased due to gross miscalculations of the military departments in determining the real needs of the army and the traditional “squeezing” of funds by the Ministry of Finance. Therefore, the increase in the production of weapons and ammunition, especially in the first year of the war, occurred with glitches, chaotic, but still generally dynamic. Painful interruptions began primarily in the supply of small arms to the active army: rifles and machine guns.”

The father of the current Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation on the reasons for the transport and energy collapse in the Russian Empire: “During the war, all imports were delivered by sea to Arkhangelsk and Vladivostok, where they were loaded onto the railway. But the infrastructure of these ports was not able to handle the sudden influx of large-tonnage cargo traffic. Even valuable cargo accumulated here in huge quantities and lay there for months, and sometimes years, deteriorating and becoming ownerless. Naturally, there was no room left for coal. Thus, Russia suddenly missed 7–7.5 million tons of valuable fuel.”

Of course, in more than a hundred years, not just a lot has changed, but a lot has changed. The First World War and the Northern Military District are fundamentally different armed conflicts. But the main thing, it seems to me, is not the fact of grandiose technological changes, but the fact that Rem Belousov taught his son a special view of the world. Politically, Belousov Sr. was not a pacifist, but an absolute realist: “The major powers of the world entered the twentieth century with a pile of contradictions and a readiness to fight with each other… Essentially, it was about a new redistribution of world resources and spheres of influence. It is usually not possible to reach agreement on such issues without a violent struggle.”

But in the same way, Andrei Belousov’s father was not a militarist or a supporter of permanent conflicts. For example, this is what he wrote about the main challenge that our country had to constantly struggle with throughout the twentieth century: “Among limited resources, the most scarce was time. The fact is that out of the hundred years that Russians had at their disposal in the 20th century, more than a third was spent on wars and eliminating their consequences. There was something to think about: you can’t get time back or stretch it out. To catch up with those who had gone ahead, there was only one means — to increase the speed, that is, the pace of economic development. Such a maneuver is always associated with a risky overheating of the economic mechanism and social system.” The challenge that Russia will have to contend with in the 21st century seems to have remained the same. However, Andrei Belousov, who is at the forefront of this struggle, has one important advantage: he clearly understands what he has to deal with and clearly knows what he wants to achieve.

During the period when Andrei Belousov was growing up and developing as a person (for understanding: the current Minister of Defense was born in March 1959), there were three main informal ideological trends in Soviet economics. Some still believed in the bright future of socialism and believed that if the usual Soviet model was repaired, reformed and improved, it would have a chance to put capitalism in its belt. Others used the rhetoric of the “socialist choice” as a camouflage to cover their absolute orientation towards Western economic practices. But the third — ideological predecessors and mentors of Andrei Belousov — this is perhaps the most interesting and unexpected.

If you don’t know the real state of affairs, then an organization called the Economic Institute of the USSR State Planning Committee can easily be considered a nest of economic orthodoxy. But as I hinted in the previous sentence, the reality was very different. Gosplan was the main headquarters, the main command center of the Soviet economy. And in order to perform these functions, the leadership of the State Planning Committee needed a clear understanding of what was actually happening in this economy. This determined the difference between the ideologists of the “third way” supporters based at the State Planning Research Institute and the two other groups. This is how this difference was formulated for me by a very knowledgeable person who is familiar with the subject of conversation in detail.

“As ideological opponents, the proponents of building socialism with a human face and the romantic marketers were very similar to each other in one key respect: both saw the economy not as it is, but as it should be in its ideal form. The Gosplan Research Institute took the opposite position — one must start from what actually exists, and not from how everything should be in some fictional world.»

Later, supporters of this view of the world grouped together in the Institute of Economics and Forecasting of Scientific and Technological Progress of the USSR Academy of Sciences, founded in 1986. Today this organization has a slightly different name: Institute of National Economic Forecasting of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Andrey Belousov worked here for many years. It was here that he formed as a scientist and practitioner. It was here that he formulated his ideological credo. As things stand at the moment, I interviewed Andrei Belousov twice in different years and am very pleased with the result. However, I am forced to admit the obvious: the current Minister of Defense formulated his ideological credo to the greatest extent during an interview not with me, but with competitors — the RBC agency — in the summer of 2023. Let's get acquainted with this credo. Andrei Removich is a person for whom Russia is, of course, at the very center of the “ideological universe”: “Russia can become the custodian of the traditional values of the West. While the West said goodbye to these traditional values and moved on to something else, which is actually anti-tradition within the framework of postmodernism.”

Andrei Belousov is a prominent representative of that very narrow stratum of economists for whom progress in the country’s development is not limited to economic issues alone: “We have our own cultural code. Their own cultural identity, which the vast majority of countries and peoples do not have… By the way, Dostoevsky felt it very well. Dostoevsky’s pathos, especially in such a work as “The Diary of a Writer,” is expressed there in a simply 100% refined way… This is our main resource, we need to pull it out.”

The current Minister of Defense is a staunch supporter of a market economy, but not in the version of the 90s, when big oligarchic business dictated to the state what it should do: “How should the state build relationships with business in the new conditions strategically? I believe that we should become partners… A senior partner and a junior partner. Because in our conditions the state is not a night watchman or even a balance between society and the state. The state takes on many of the functions of civil society… Therefore, there cannot be equality between the state and business.”

And finally, the last thing — in order, but by no means in importance. Andrei Belousov is a categorical opponent of extreme measures in the economy without absolute necessity. Another interview of the then First Deputy Prime Minister of the Russian Federation to competitors (this time from TASS, June 2022): “The mobilization economy means the suffering of millions of people. This is always the suffering of millions of people. Are we ready to pay this price to break through somewhere? It doesn't happen any other way. Remember the 30s, 50s, what did the village turn into? We finally finished it off; all our problems in the 70s largely began due to the fact that our village began to degrade very quickly.”

And here is another statement by Andrei Belousov about the mobilization economy — a statement that, in my opinion, explains Putin’s entire current strategy: “I don’t know of a single case in the world when the mobilization economy — after all, not only Russia, a number of other countries passed through this — whenever this mobilization passes through generations. Usually the mobilization period is from 10 to 20 years, maximum 30 years.” It would seem that 30 years is a very long time. But let's remember how long the first Cold War lasted. Winston Churchill's Fulton speech with his Iron Curtain rhetoric, 1946. Moscow's refusal to respond forcefully to a series of falls of pro-Soviet regimes in Eastern Europe, 1989. Even if we take this narrow framework, it turns out to be 43 years — almost a third more than the maximum capabilities of the mobilization economy.

Of course, we do not know and cannot know how long the second Cold War will last. But we can be sure that it will continue after the end of the SVO. The West believes that Russia has thrown down a dueling gauntlet and is determined to give it a worthy response. If we discard catastrophic scenarios, then we are talking about a period “long” of generations. And here the main lesson of the first Cold War becomes relevant again — such geopolitical battles are won and lost not only “at the front” (or at the front without quotes).

They are also won and lost in the rear. Economic “normality” — decent living conditions for people, economic growth, the country’s openness to the global world to the extent possible in conditions of confrontation with the West — all this is also a “weapon”. In order to withstand the onslaught of the richest and most powerful enemy in the world during the second Cold War, Russia will need the entire range of this “arsenal”.