«We have a low quality of human capital»

Tectonic shifts continue in the depths of the Russian labor market, caused by shocks of 2022 unprecedented in scope and specifics. The departure of Western employers, at least two waves of emigration, the beginning of the «structural transformation» of the economy, the breakdown of supply chains — these and other events launched the process of reformatting the entire employment sector. Its key problem remains an acute shortage of qualified personnel, which is indirectly evidenced by the record low unemployment rate. We talked about this with Doctor of Economic Sciences, Professor Evgeny Gontmakher.

— Several factors came together. The main thing is demographic aging, and this trend will continue regardless of the development of the geopolitical situation. In 2022, it was superimposed by two events related to the NWO — a surge in emigration and partial mobilization. According to various sources, from several hundred thousand to a million people of active working age left Russia. Later, some number returned, but the balance is still in favor of the relocators. In addition, according to official figures, 300 thousand citizens were mobilized, mainly from villages and small towns, from economically backward regions. Many residents of the province went to the front voluntarily: for their families, a salary of almost 200 thousand a month is unprecedented money, plus something is paid extra by the regional authorities. These people temporarily dropped out of the labor market, unlike some of those who left, the same IT people who remotely produce some kind of product in Russia.

— A catastrophe is when an event occurs at lightning speed, turning reality 180 degrees. Now there is no such thing. We are talking about long-term trends, the consequences of which will manifest themselves years later and not all at once. People drafted into the army do not produce GDP. For the economy, this is a potential loss of minus one percentage point of GDP per year, which, however, is not critical. In case of departure, the negative effect is even smaller, since many relocators, being at a distance, continue to work for Russia. However, if we talk about the mobilized, after returning from the SVO, they will need rehabilitation — social, professional, psychological, some of them — medical. It will take some time for them to return to the labor market, to restore social ties. And it is quite difficult, as the experience of Afghanistan and Chechnya has shown.

In general, Russia is a huge country, with very different regional characteristics, a universal approach to it is not applicable, it is impossible to operate only with average statistical indicators. For example, emigration had practically no effect on the labor market in the capital. The vacated jobs were immediately taken by those who came from other regions. But in the provinces, the shortage of not only highly qualified personnel, but also simply workers, has become aggravated. Suppose there were 20 combine operators in some agricultural enterprise, 10 of them left due to mobilization. And on the nose sowing. And how to be? There are many such potential vulnerabilities in the economy, they should be dealt with by the state and, in particular, the Ministry of Economic Development, the Ministry of Labor, local authorities.

— There is no contradiction in the very thesis about the shortage of personnel, the word “qualified” is simply missing. In our country, due to unfavorable demographics, the number of able-bodied population is declining by several hundred thousand people a year. There are fewer people between the ages of 14 and 65, which, in turn, creates fertile ground for lowering the unemployment rate. There are jobs in the country. There are more vacancies on recruiting sites than applicants' profiles. The problem is different, and employers have been talking about it for many years. When businesses are asked what prevents them from developing in the first place, the most common answer is “an acute shortage of qualified personnel”. In the economies of the vast majority of countries — and ours is no exception — the process of displacing monotonous hard work with advanced technologies and robots has long been going on. Laborers are no longer needed. At the same time, jobs remain where qualified specialists and production organizers are needed — managers who cannot be replaced by any artificial intelligence.

— Personnel imbalance is caused by distortions in the Russian system of vocational education, which responds very sluggishly to the demands of the labor market. For example, we have a colossal shortage of engineers, although there are enough state-funded places in technical universities where they are trained. There was a certain general mental attitude that engineering work is not prestigious. It is prestigious to be, for example, a manager — they say, you sit in the office, manage the team, drink tea and coffee, get a decent salary. Or civil servants who are guaranteed not to be fired. IT people are always popular. A person thinks that if he masters this profession, he will automatically provide himself with a good income. Which actually doesn't always work. At the same time, the system of vocational education often does not provide the necessary competencies. Of course, in Russia there are advanced world-class universities, but for the most part, institutions churn out graduates with meaningless diplomas. Millions of people do not work in their specialty, doing, in fact, unskilled labor and worsening the situation on the labor market. They are kept at work, paid a penny and are afraid to be fired, because in our country this is a political issue. And this is a big problem, which largely hinders the growth of the economy.

In addition, there is no practice of affordable retraining. Yes, there are courses on the Internet, at universities, but Russians, even relatively young ones, do not have the habit of retraining once every three years, gaining new skills. The old Soviet attitude sits in the mind — once you have received a diploma of higher education, this is for life. Something needs to be done about this, we need to encourage employers to invest in the retraining of workers. Maybe compensate them for the costs from the budget. With regard to mobility, we have a long-standing trend in the flow of personnel from villages and small towns to large cities, which provide much more opportunities. Territorial mobility is quite high, especially among young people. The problem is that in Russia there is no intersectoral mobility — this is when a person, having worked for some time in his specialty (even within the same city or region), then retrained somewhere and began working in a new specialty, then again changed his occupation and so on. Our people do not know how to flexibly change their professional profile, and there is no corresponding educational infrastructure.

— The state has clearly won in terms of budgetary savings, since the number of pensioners has decreased over the past two or three years. The financial burden on the Social Fund (former Pension Fund) has decreased in relative terms. The absolute figures of spending are still growing, but not as fast as if there were no increase in the retirement age. The state initially set such a goal — to save, reduce the cost of the treasury. She has been reached. As for the sphere of employment, there is more likely to be a loss here, since the category of workers engaged in unskilled and low-paid work has grown quantitatively due to pre-pensioners. Many of these people are forced at the end of their careers, not yet retired, to get jobs as security guards, cloakroom attendants, cleaners … Because when a person is over 50 and does not have the skill to regularly retrain, he hopelessly lags behind the requirements of the modern labor market, flies out to its side.

This is exactly the case with mass technical professions, in contrast to a part of the humanities: scientists, journalists, teachers who are able to work productively at any age, if they have everything in order with their head and health. That is, in this case, the increase in the retirement age in 2019 played the role of stagnation, since this measure expanded the zone of inefficient employment. Why are salaries low in Russia? Not at all because the enterprises do not have the necessary equipment or high-performance management. And because the bulk of the staff is poorly qualified. And this is the number one problem, not unemployment.

“Obviously, there has been no radical improvement in their financial situation. Although the authorities initially stated that pensions would be increased precisely at the expense of the savings. At the level of official inflation, yes, pensions have been raised. However, we must not forget: inflation is always higher for pensioners than for other groups of the population. Food, for which (apart from housing and communal services) they mainly spend their money, is becoming more expensive in Russia faster than other goods. With regard to young people, skepticism towards the pension system in this environment has clearly increased. The essence of the insurance pension system is the ability to save in advance for old age from wages (the employer pays insurance contributions to the Social Fund for employees). For young people, this motivation was weak before, and with the increase in the retirement age, it has practically disappeared. It is clear why: in May 2018, the measure was announced, and in the fall, the State Duma already laid down a legislative framework for it. Some 20-year-old person looks at this and thinks: I am over 40 years old before retirement, the rules of the game can be changed a hundred more times. And then what's the point of worrying about replenishing your account in the Social Fund? I note that both in the USSR and in Russia, the retirement age has never been raised before. The figures of 60 and 55 years have been considered sacred since the post-war period. The law on state pensions was adopted in 1956, and these levels were fixed there. Alas, unlike France and other Western countries, today we do not have a culture of searching and finding a compromise in such matters between the state and the population.

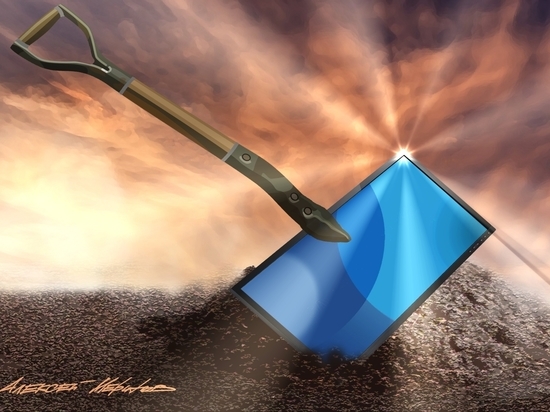

— Sooner or later, the investment process will resume in the country. The country will return to peaceful development, conditions will be created for economic growth, technologies and equipment will be purchased. But where to get people under it? Moreover, we may well nominally have enough jobs and workers, this is not the point. The problem, I repeat, is the shortage of specialists with the necessary qualifications. It's like in the Lego constructor: its plastic elements must be easily and firmly connected to each other using grooves — this is the only principle. The economy is moving forward, processes are accelerating, including in the labor market. New vacancies require specific competencies. And here we need an automatic, self-regulating system, we need institutions that can quickly adapt to the changing reality. Manual mode is ineffective. The low quality of human capital is seen as the main obstacle to Russia's development. About 10 years ago, the country somehow developed at the expense of oil and gas, bought a lot of things abroad, and now the situation with the export of raw materials and foreign trade as a whole is getting worse. This means that Russia should take a different economic path, find a new niche for itself, ideally, make a technological breakthrough. But the “bottleneck” remains, in particular, the education system, which has not been calibrated to the needs of the real sector of the economy. In addition, we have a rather sick — in the truest sense of the word — population (largely due to systemic flaws in the healthcare system), and life expectancy lags far behind those in developed countries.

< p> — The main effect caused by covid is the remote mode, to which many sectors have switched. As it turned out, from an economic point of view, this is quite normal and absolutely does not worsen the quality of work of enterprises and organizations. On the contrary, remote people have become more productive due to increased convenience: here is the bed, but the computer is a meter away from it; working day and rest time are no longer so sharply contrasted with each other. During the pandemic and lockdowns, inefficient (on the verge of profitability) enterprises were rejected, many jobs were closed, especially in the service sector. Of course, in terms of human destinies, there is little good here, but from the standpoint of the economy, it was a kind of purification. “Crisis” is a Greek word, which in translation means, among other things, “turning point”, it is not only a disaster, but also new opportunities. Whether we will be able to use them when the painful geopolitical factor leaves our lives is a big question.