Scientists continue to find answers to the extinction of ancient man

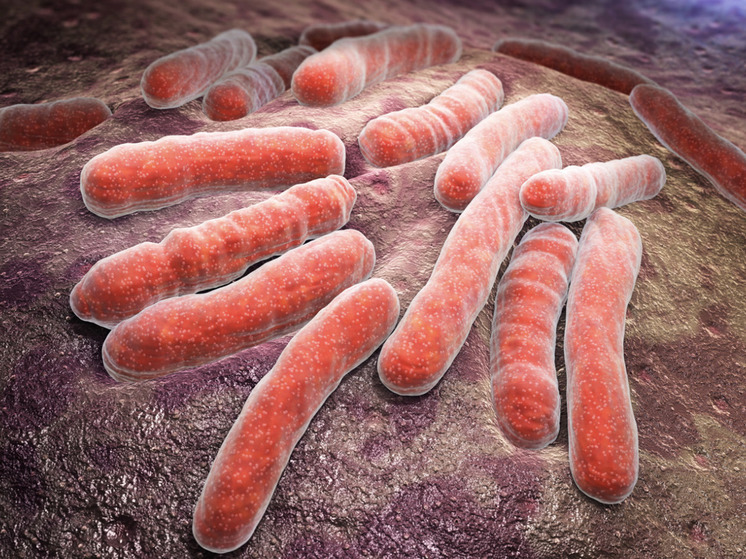

Neanderthals who lived in Central Europe about 35 thousand years ago suffered from tuberculosis, a new DNA analysis of their bones has shown. This is the first time the disease has been identified in an ancient human, raising questions about whether tuberculosis contributed to their extinction.

In two scientific studies published in the journal Tuberculosis, an international team of researchers analyzed the skeletal remains of two Neanderthals discovered in a cave in Hungary in 1932, and another checked them for the presence of the bacterium that causes tuberculosis.

Subaluk Cave, located in the Bükk Mountains in northern Hungary, has been repeatedly used as a refuge by animals and humans over the centuries and is considered an extremely important Middle and Late Paleolithic site. The bones found near the entrance belonged to an adult woman and a child approximately 3-4 years old at the time of death.

Researchers have long speculated that the remains represented some of the last Neanderthals in central Europe. Radiocarbon dating of the remains in early 2023 confirmed that the child died about 33-34 thousand years ago, while the adult died earlier, about 37-38 thousand years ago. The remains provide additional information about their lives and deaths.

“Signs of skeletal infection were found in both Neanderthals, including bone lesions along the adult spine and on the inside of the child’s skull,” the experts said in the report.

These skeletal changes, called lytic lesions, reflect bone loss, which results in the formation of holes that are filled with new bone. These types of metastases can occur due to a number of diseases such as cancer, and their location and structure in the bodies of Subalukian Neanderthals strongly suggests a diagnosis of tuberculosis, said a team led by Gyorgy Pálfi of the University of Szeged in Hungary.

To test this diagnosis, a research team led by Una Lee from the University of Birmingham in the UK took bone samples from two skeletons and analyzed them for DNA from the bacteria that causes tuberculosis. Both were positive.

“Based on both the morphological observations and their biomolecular support, we can conclude that tuberculosis was widespread in Central Europe during the late Pleistocene, approximately 36-39 thousand years ago,” — Palfi told.

The discovery of tuberculosis in Neanderthals raises an additional question: how did they contract it? Evidence of tuberculosis in large animals throughout ancient Europe, especially bison, suggests the answer: Neanderthals, who hunted and consumed these animals, probably contracted tuberculosis from them. Thus, the disease was dangerous «both because of the direct health risks and the destruction of carnivore populations,» Lee concluded.

Palaeopathologist Corey Filipek told Live Science that the research «provides interesting approach beyond our own species' understanding of disease» and that they «may provide insight into how human behavior has allowed these pathogens to invade our disease landscape.»

However, Filipek cautioned that research should always be done first comprehensive non-destructive analysis, «especially given the rarity of the Neanderthal material.»

Future developments in this direction could provide new evidence of the diseases that affected Neanderthals and perhaps the reasons why they went extinct, the research team said.