The dilemma can be easily resolved if the population's real incomes are growing

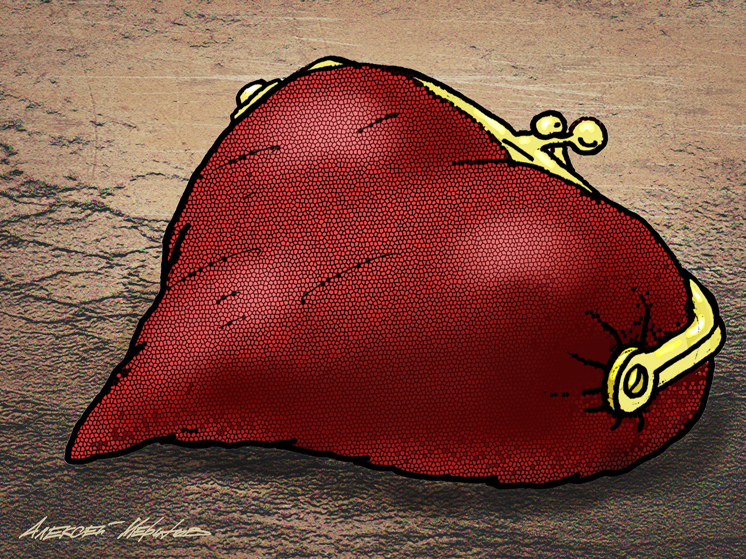

Despite the Bank of Russia's remaining high key rate of 16% per annum from December 2023, consumer price inflation continues to rise. The Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation estimated the increase in inflation in June of this year by more than 9% in annual terms. The Bank of Russia no longer even hints, but openly declares that the key rate will be raised at the next meeting of the board of directors on July 26.

As is known, high interest rates make credit less accessible, which means that businesses have limited opportunities for investment and future development, which, accordingly, can become a brake on economic growth. And in this context, the question arises: is it even necessary to fight inflation in such an ambiguous way as raising interest rates?

Of course, in Russia, and nowhere else in the world, they do not want inflation to completely get out of control and transform into hyperinflation, completely depreciating the national currency and household incomes. By the way, this is exactly the situation now in Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, Lebanon and Argentina, where as recently as 2023, consumer price inflation exceeded 200% per year. However, you can pay attention to the experience of some countries friendly to the Russian Federation, where even high inflation turned out to be not at all an obstacle to economic growth and did not have a too destructive effect on the standard of living of the population. For example, in Turkey, inflation reached 65% in 2023, and in Iran it exceeded 44%. At the same time, Turkish GDP grew by 4% last year, that is, more than in Russia, whose economy added only 3.6%, and, despite high inflation, at the end of last year, Turkey became the thirteenth economy in the world in terms of GDP, calculated at parity purchasing power (Russia was fifth in this ranking).

We also note that in 2021, that is, in the first “recovery” year for the entire world economy after the end of the most acute phase of the pandemic, the growth of the Turkish economy was 11.35%. In 2022, Turkey's GDP grew by almost 5% during an acute crisis in the global economy, which, among other things, led to rising energy prices. High inflation, despite its negative impact on the exchange rate of the Turkish lira and the real incomes of a significant part of the population, is, in principle, not an obstacle to the growth of the Turkish economy. The country makes money from tourism and the export of food, light industry products and especially mechanical engineering, which, in our opinion, Russia should pay special attention to. High inflation depreciates the national currency, and this benefits both exporters and the tourism industry, which in Turkey is the same national treasure as oil and gas in Russia. The more tourists there are in the country, the more opportunities local businesses, including small and medium-sized ones, have to earn money, which means increasing wages for employees in order to smooth out the negative consequences of rising inflation. For these reasons, Turkey has developed a special economic model in the last decade — “Erdoganomika” (named after Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan), when the authorities do not attach much importance to the fight against inflation, but instead pay more attention to stimulating economic growth. Let us also note that in Turkey over the past 14 years, despite the fact that the world has experienced four economic crises during this time, there has been no economic recession, although with high inflation of tens of percent per year, Turkey has had to live for a very long time, since the 90s XX century.

Iran, one of the largest countries in the world in terms of hydrocarbon reserves and production, in turn, has been living under Western sanctions and the oil embargo for decades. Nevertheless, in 2021–2023, the economy of this country grew by an average of 2.5–4.5% per year. These are not the highest growth rates when compared with China or India, but higher than in Russia and comparable to the pace of the global economy. At the same time, Iran has been living for many years with high inflation, which exceeds 40% per year. Moreover, the specific reason for high inflation in Iran is not so much sanctions as the country’s dependence on the supply of grain crops — after all, interruptions in these supplies directly affect the cost of food, which is one of the key generators of inflation growth. At the same time, in Iran, in order to smooth out the negative consequences of increased inflation for the population and businesses working only on the domestic market, the central bank keeps the exchange rate of the national currency, the rial, fixed.

Thus, based on the experience of Turkey and Iran, one can see that the authorities of these countries do not bother fighting inflation at any cost, but instead attach decisive importance to economic growth. In turn, the G7 countries, which continued to fight inflation exclusively by continuously raising interest rates, have been showing a slowdown in growth rates since 2022. In the United States, economic growth in 2022–2023 was only 2.1% per year, which turned out to be lower than the world rate over these years, and the economies of the eurozone and the UK completely stagnated, showing GDP growth close to zero.

Well, if other Russian countries are not an example, then you can turn to your own experience. In 2003–2007, against the backdrop of unprecedentedly high oil prices, Russia showed GDP growth rates of 8–8.5% per year. And consumer price inflation then amounted to a “terrible” by today’s standards of 11% per year — on average. And at the beginning of the 21st century, inflation in Russia was 15–18% per year, but this did not prevent the Russian economy from “getting off its knees” and starting to grow after almost a decade of recession. Some economists at that time even argued that with double-digit inflation rates, Russians would have to live for a long time, but there was nothing tragic about this if there was economic growth and rising wages. At the same time, according to Rosstat, the real incomes of Russians have grown by an average of 11–12% per year since the beginning of the century.

Since 2013, the Bank of Russia began targeting inflation, setting a goal for the growth of consumer prices in the country by no higher than 4% per year. Real incomes of Russians reached their peak growth just in 2013, and even the unprecedentedly high growth rate of this indicator in 2023 in 2023 could only bring real incomes of Russians to a level of 98.3% of the 2013 level. In 2017–2019, inflation in the Russian Federation slowed to approximately the target level of 4% on average, but such record low inflation was accompanied by unprecedentedly low growth in real incomes of Russians. Simply put, inflation in the country has slowed down to the target level (target) of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation due to the low purchasing power of a significant part of the population. And Russian GDP in 2017–2019, with such low inflation, did not show any outstanding rates, growing only 1.8–2.2% per year.

Thus, in our opinion, the dilemma “which is better — high inflation or high rates of economic growth” is resolved very simply if the population’s real incomes are growing and (most importantly!) if the national currency exchange rate is stable.

For Russia today, since its economic model is changing towards greater priorities for the manufacturing industry, technology and industries working for the domestic market, maintaining high growth rates would be very important. This means that high interest rates, which help to curb excessive activity of the population in the debt market, should not be sky-high. Of course, rising inflation is not a benefit for either the population or business, since a collapse in the purchasing power of the population is certainly not a gift for either the population itself or the economy as a whole. Therefore, it is too early to discount the monetary methods of fighting inflation by raising the interest rate, which have proven themselves over many years and in many countries around the world. But raising the key rate every time inflation rises by half a percentage point per month is also not the best option.

There are other ways to fight inflation besides raising interest rates, for example, reducing excessive government spending (of course, there can be no talk of the state's social obligations, defense capability and security of the country). There are also other ways of financial support for the real sector of the economy when interest rates are high, for example, the Industrial Development Fund of the Ministry of Industry and Trade, preferential taxation of key industries, industrial mortgages…

It is quite possible to achieve high rates of economic growth while simultaneously stabilizing the growth of consumer prices if you use the experience of other countries, and not necessarily Western ones, your own successful experience of past years, and combine traditional methods of combating inflation with less standard ones. And, of course, put the growth rates of real incomes of the population at the forefront.