How to reduce the gap in the welfare of the richest and poorest Russians

The main factors of a country's economic potential are traditionally considered to be its labor resources, capital and natural resource rent. However, 21st century economics increasingly emphasizes the role of cultural norms (generally accepted rules of doing business) and institutions (mechanisms that ensure compliance with these norms). The motivations of participants in economic processes and the effectiveness of their interaction primarily depend on them. They themselves are determined by the historical memory of society and the quality of public administration.

Management is based on policy — a list of tasks that are prioritized for the managed system. For example, according to the “Main Directions of Budget, Tax and Customs Tariff Policy for 2023 and the Planning Period of 2024 and 2025”, in order to create stable and predictable economic and financial conditions in Russia, it is necessary to ensure the stability of the real exchange rate of the ruble, the price structure in the economy, low inflation and tax conditions, as well as low interest rates on long-term resources (read — mortgages).

Neither in this nor in other strategic planning documents did I find a word about state income policy, that is, about the tasks of redistributing them through taxes and budgets between population groups with different levels of well-being. It seems that the federal authorities do not set such tasks at all.

Meanwhile, the question of income distribution — this is not only about fighting poverty and preventing social conflicts based on inequality. An international study commissioned by the IMF showed that income policies that reduce economic inequality in a country lead to significant growth in its GDP — the main indicator of economic growth.

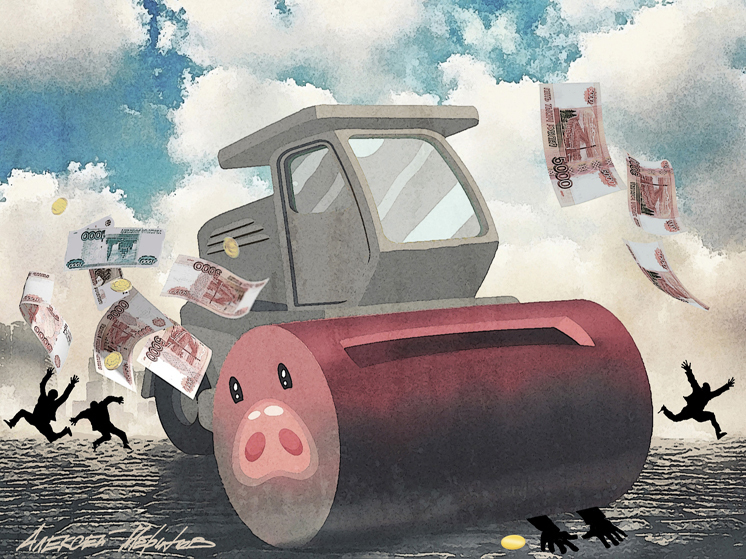

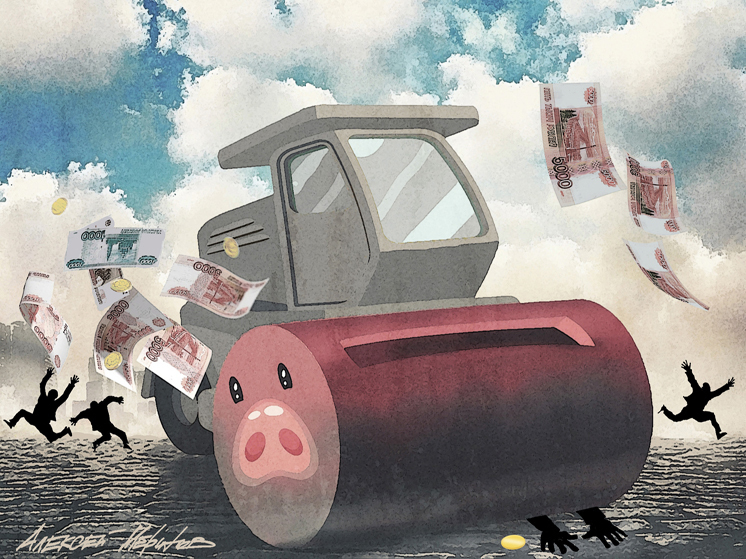

Having analyzed the relationship between GDP and the distribution of total income of the population between five groups of equal size (from the poorest to the richest) over three decades in 159 countries with different levels of economic development, scientists saw that an increase in the share in the “total pie” Any group except the richest will see significant GDP growth over the next five years. Moreover — the more significant the poorer the group whose share has become larger. However, an increase in the share of income of the wealthiest twenty percent of the population, as it turns out, has the opposite effect: GDP decreases slightly.

This result is easy to explain. The poorest spend their additional income almost entirely on purchasing what they desperately need, but previously could not buy due to lack of funds. Wealthier citizens have fewer unmet needs, so part of their additional income goes into savings and is not reflected in GDP. The increase in the share of the richest group has very little effect on its expenses, but since the «pie» is common, this increase is provided by the share of income of the poorer groups, which entails a reduction in their expenses reflected in GDP.

So, it is economically beneficial for the state to reduce income inequality. Why then are its program documents silent about this? Perhaps this is not relevant for Russia: the income gap is low by global standards and is steadily decreasing?

Alas, this is not the case, and has not been for about thirty years. In 1990 — the last one before the collapse of the economic structure and management system — in the total income of the population of Russia, the share of twenty percent of the least wealthy citizens was one tenth, and the share of the same number of the most wealthy — one third. Five years later, in 1995, the share of the poorest group became half as much, and the richest — one and a half times more: parts of the shares of less affluent groups flowed to it, and the poorer the donor group was, the greater the share of its income went to the “upper level”.

Such a radical redistribution of income, the peak of which occurred in 1991–1992, when savings and current incomes depreciated massively, became one of the factors in the steady decline in GDP (in 1991–1998 — annually by an average of 6–7 percent) and, I believe, contributed to it because the decline in consumer demand of most citizens due to a sharp reduction in their income was not compensated by the increase in demand from the wealthy beneficiaries of this redistribution.

I am sure that the negative impact on the economy in those years of a sharp increase in mortality, especially among men, associated with the rapid impoverishment and loss of status of a large number of citizens, was no less strong. In 1995, a third more men died than in 1990, and mortality increased from almost all causes except oncology, but especially strongly — from «external» reasons, including suicide — one and a half times, murders — doubled, alcohol poisoning — three times.

The income distribution that emerged in Russia by the mid-1990s has changed very little to date. If in 1990 the ratio of average incomes in the two extreme groups was slightly higher than three, as in the Scandinavian countries, where economic inequality is minimal, then over the last 30 years this figure has fluctuated between 8 and 9, which allows Russia to be classified in world rankings as countries with a high level of economic inequality.

This is all about the country's averages. But people live in a specific city or region, which can vary greatly in this regard, so it is reasonable to talk about the regional projection of economic inequality. Moscow clearly stands out here, where the average per capita income is more than twice as high as in the country as a whole, and almost three times higher than in the rest of Russia. This applies to all income groups, and the richer the group, the greater its gap from the Russian average. Accordingly, polarization is higher here: the average income in the richest group is 9.5 times higher than in the poorest.

According to official data, every eleventh citizen of our country lives in Moscow. But among the 20 percent of Russians with the lowest incomes, Muscovites are six times less common. But among the 20 percent of the richest residents of Russia, every fourth — Muscovite And of the five percent of the country’s wealthiest people (Rosstat also takes them into account), almost every second person lives in Moscow — five times more than if the rich were distributed evenly across the country's regions. However, among residents of the Volga, Southern and Siberian federal districts they are found 2-3 times less often, and in the North Caucasus — five times less often.

Five percent of the population — this is more than seven million people, and three of them live in Moscow. Rosstat does not report on the internal structure of this group, but I remember that in the mid-1990s, an authoritative economist argued that in the bell-shaped distribution of the Russian population by income, which was usual for most countries at that time, there was a small bell in the “tail”, where the incomes of the richest were taken into account citizens, testifies to the existence within Russia of an invisible subcountry with its rich, poor and middle class, a kind of premium Russia.

But in the Vladimir region bordering Moscow, the average income is three times lower than Moscow and one and a half times lower than the Russian average. But the polarization here is much lower (the ratio of the incomes of the extreme groups is less than six), and the poor in Vladimir are more than double, and the rich in Vladimir — more than three times poorer than those who have the right to be called that in Moscow. So if a referendum on annexing the region to the capital were held here, I think only a few top regional officials would vote against, losing their positions. Or maybe they would have voted for it. But Muscovites would hardly agree.

Over the decades, we have become accustomed to economic inequality, and if we even think about it, it is rather as something unpleasant, but beyond our control. But this is not so: it is quite possible to reduce it, it has been done and is being done in many countries, especially successfully — in Scandinavian. And in recent years, we have actually begun to do this, increasing subsidies to the poor within the framework of social policy, and within the framework of tax policy — seizures from the rich. But these measures are aimed at solving other problems and are not interconnected — reducing inequality for them can only be a side effect.

Russia needs a public income policy that can stimulate economic growth, while entrenched, unjustified and uncontrolled inequality holds it back and leads to a decline in the quality of the country's human capital.